The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

Much of the commentary around the issue also maintains that we (that is humans) have always known the difference between men and women. It also maintains that the definitive test for femininity is the possession of XX chromosomes, as opposed to XY for men. This is despite the fact that sex chromosomes have only been known to science since 1905, and that many humans are known to have chromosome patterns that are neither XX nor XY.

Of course if you are an historian who specializes in gender diversity (which I am) it is important to understand how people in the past understood sex and gender. There is no greater expert on such issues than Helen King. She’s a Classicist by training, and Professor Emerita at the Open University. Her particular specialty is the history of medicine, and her latest book, Immaculate Forms, takes her on a quest to understand how the female body was understood from ancient times until now.

King has structured the book in four main sections, each of which looks at four supposedly feminine body parts: the breasts, the hymen, the clitoris and the womb. I’ll follow her structure here.

Breasts are, of course, the most obvious signifier of womanhood, being both large and visible. It is significant, therefore, that the anti-trans movement has made it an article of faith that only cis women can have them. Trans women, they claim, can only gain breasts through having implants. King knows better. Breast tissue is common to both men and women, and with appropriate doses of hormones trans women not only grow breasts, but can lactate. I have been roundly ridiculed on social media by TERFs for stating this, so it is something of a pleasure to have support from Professor King.

Men are also deeply obsessed with breasts, for entirely different reasons. King does a fine job of showing how, down the centuries, male doctors found excuses to fondle women’s breasts, and even sample their milk, all in the name of ‘science’. The clergy have had a harder time of it. Did the Virgin Mary have breasts? If so, did she lactate, and did baby Jesus suckle? For some that was just too icky to contemplate.

Whereas breasts are famed for their visibility, the hymen may not exist at all. King refrains from coming down on either side of the debate, if only because hymen-replacement surgery for divorced women is now apparently big business in certain parts of America. If the hymen did not exist in the past, it certainly does now. And, whether or not it did exist, the concept of the hymen has had a massive influence on women’s lives through history.

In contrast, we can be certain that the clitoris exists now, because so many male doctors claim to have been the first person to discover it, rather in the manner that Columbus claimed to have discovered the Americas. Women, like the indigenous Americans, have known where it is all the time.

Of all the female organs, the womb is undoubtedly the most powerful. Not only is it responsible for nurturing new life, it has also been accused of being the source of all manner of female ailments down the years. Hysteria, anyone?

Well actually no. The ancients were big on how the womb might wander around the body, and how it might get hungry and angry if it were not made pregnant on a regular basis. However, the mental illness of hysteria, which we now associate solely with women, was once a more general condition.

King reveals that the term was coined as a mental illness in 18th Century France. Frightened aristocrats found that, if they were diagnosed with a mental illness and confined to a nursing home, they might be spared the guillotine. Hysteria only became a women-only condition after WWI because it was felt that diagnosing soldiers with such a term impugned their masculinity; so ‘shell-shock’ was coined as an alternative.

While a certain type of man only values women as long as he can make them pregnant, we now know that even possessing a womb is not a definitive indicator of womanhood. King notes:

Of course, not all women have a womb; some are born without one, others lose it to surgery, and others have transitioned to being women.

For those wanting more background, the intersex variation that results in a woman being born without a womb is called Mayer-Rotikansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. King notes that at least one such woman has successfully received a womb transplant and become pregnant using her own eggs.

So it is complicated. How one defines a ‘biological woman’ is open to debate, has changed regularly with changes in medical knowledge, and will always end up excluding some people who were assigned female at birth. King notes:

These modern methods of appealing to chromosomes and hormones, features of our embodiment that others can’t easily see and of which we are entirely unaware, can still prove far from conclusive in deciding whether someone is a man or a woman, and we rapidly revert to the evidence of our eyes. Culturally, we continue to crave binaries.

And yet…

Men and women have been set up as entirely different, with their bodies claimed as bearing clear witness to this. But one of the messages from studying bodies across history is that, while the dance between describing difference and acknowledging similarity has been going on for centuries, binaries simply don’t work.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the Supreme Court and the government continue to refuse to listen, either to history or to science.

Title:

Title: Immaculate Forms

By: Helen KingPublisher: Wellcome Collection

Purchase links:Amazon UKAmazon USBookshop.org UKSee

here for information about buying books though

Salon Futura

This is the July 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the July 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Cover: The Jicker Man: This issue's cover is The Jicker Man by Ben Baldwin

Cover: The Jicker Man: This issue's cover is The Jicker Man by Ben Baldwin Lords of Uncreation: Adrian Tchaikovsky's Final Architecture trilogy comes to its dramatic conclusion

Lords of Uncreation: Adrian Tchaikovsky's Final Architecture trilogy comes to its dramatic conclusion Mythica: Emily Hauser takes a fresh new look at Bronze Age Greece through the lens of the women in Homer's poems

Mythica: Emily Hauser takes a fresh new look at Bronze Age Greece through the lens of the women in Homer's poems Murderbot – Season 1: What happens when one of your favourite book series gets adapted for TV? Cheryl gets to find out.

Murderbot – Season 1: What happens when one of your favourite book series gets adapted for TV? Cheryl gets to find out. Ironheart: Riri Williams gets her own TV series. Can a teenage Black girl be a superhero? Well...

Ironheart: Riri Williams gets her own TV series. Can a teenage Black girl be a superhero? Well... The Fantastic Four – First Steps: Every previous Fantastic Four movie has been a flop. Can the MCU save Marvel's First Family?

The Fantastic Four – First Steps: Every previous Fantastic Four movie has been a flop. Can the MCU save Marvel's First Family? Archipelacon 2: This year the Eurocon returns to Finland, and we all get an excuse to spend several days in beautiful Åland

Archipelacon 2: This year the Eurocon returns to Finland, and we all get an excuse to spend several days in beautiful Åland Introducing Turku: To get to Åland from Finland you will probably go through Turku. This year Cheryl got to spend a bit more time in the city.

Introducing Turku: To get to Åland from Finland you will probably go through Turku. This year Cheryl got to spend a bit more time in the city. Doctor in the House: In which Cheryl becomes a Doctor, but does not get a TARDIS

Doctor in the House: In which Cheryl becomes a Doctor, but does not get a TARDIS Editorial – July 2025: Cheryl needs more reading time.

Editorial – July 2025: Cheryl needs more reading time. The cover for this issue is the art produced by Ben Baldwin for the Ben Mears novel, The Jicker Man. It shows the hero of the book, Ebadiah, and various other elements from the story. The central inset shows the steampunk van, Clansly, in which Ebadiah and his friends travel north.

The cover for this issue is the art produced by Ben Baldwin for the Ben Mears novel, The Jicker Man. It shows the hero of the book, Ebadiah, and various other elements from the story. The central inset shows the steampunk van, Clansly, in which Ebadiah and his friends travel north.

Reviewing the last in a trilogy of massive space opera books is a bit of a challenge. It is hard to say anything about the book to hand without giving spoilers for the previous volumes. I shall talk mostly about how Adrian Tchaikovsky has structured the book, which I think is seriously impressive.

Reviewing the last in a trilogy of massive space opera books is a bit of a challenge. It is hard to say anything about the book to hand without giving spoilers for the previous volumes. I shall talk mostly about how Adrian Tchaikovsky has structured the book, which I think is seriously impressive.

It is commonly said of writers these days that you have to have more than one string to your bow. As well as being a novelist you might work on comics, or games, or run creative writing courses, or be a journalist. Whatever pays the bills. These days the same seems to be true of academics. For example, if you are an historian, you might start a podcast, or write historical novels.

It is commonly said of writers these days that you have to have more than one string to your bow. As well as being a novelist you might work on comics, or games, or run creative writing courses, or be a journalist. Whatever pays the bills. These days the same seems to be true of academics. For example, if you are an historian, you might start a podcast, or write historical novels.

It is no secret that I am a big fan of Murderbot. Having one’s favourite fiction translated to screen is always a bit nerve-wracking, but I am pleased to say that this all turned out very well indeed.

It is no secret that I am a big fan of Murderbot. Having one’s favourite fiction translated to screen is always a bit nerve-wracking, but I am pleased to say that this all turned out very well indeed. Riri Williams is a Marvel character who is so new that I have not read any comics that feature her. I did see her guest appearance in Wakanda Forever, but that didn’t tell me much. Ironheart is a 6-episode series that focuses just on Riri, so we get to know her much better.

Riri Williams is a Marvel character who is so new that I have not read any comics that feature her. I did see her guest appearance in Wakanda Forever, but that didn’t tell me much. Ironheart is a 6-episode series that focuses just on Riri, so we get to know her much better. Several attempts have been made at a Fantastic Four movie. All of them have been reported to be flops of some sort or another. I haven’t bothered to watch any of them. As superheroes go, the FF are just not that interesting.

Several attempts have been made at a Fantastic Four movie. All of them have been reported to be flops of some sort or another. I haven’t bothered to watch any of them. As superheroes go, the FF are just not that interesting. As some of you may remember, the first Archipelacon was a Eurocon hosted by Finland with George RR Martin as the top billed Guest of Honour. It was by far the biggest thing that happened in Åland outside of a Tall Ships race. The repeat event wasn’t going to match up to that, despite having Jeff & Ann VanderMeer on board, but it was equally brilliantly run.

As some of you may remember, the first Archipelacon was a Eurocon hosted by Finland with George RR Martin as the top billed Guest of Honour. It was by far the biggest thing that happened in Åland outside of a Tall Ships race. The repeat event wasn’t going to match up to that, despite having Jeff & Ann VanderMeer on board, but it was equally brilliantly run. Whenever I go to a convention in Åland I have to pass through Turku. Normally that is all I do. My friend Otto drives me from Helsinki to Turku to catch the ferry, and drives me back again after the con. But this year was different, and I got to see a bit more of the city.

Whenever I go to a convention in Åland I have to pass through Turku. Normally that is all I do. My friend Otto drives me from Helsinki to Turku to catch the ferry, and drives me back again after the con. But this year was different, and I got to see a bit more of the city. Earlier this month I got endoctorfied. That is, the kind people at the University of Exeter bestowed upon me an honorary Doctorate of Laws (that’s an LLD, not a PhD). I wrote about it briefly on my blog, but I was still a bit gobsmacked then so I figured I owed you a longer report on the day.

Earlier this month I got endoctorfied. That is, the kind people at the University of Exeter bestowed upon me an honorary Doctorate of Laws (that’s an LLD, not a PhD). I wrote about it briefly on my blog, but I was still a bit gobsmacked then so I figured I owed you a longer report on the day.

This is the June 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

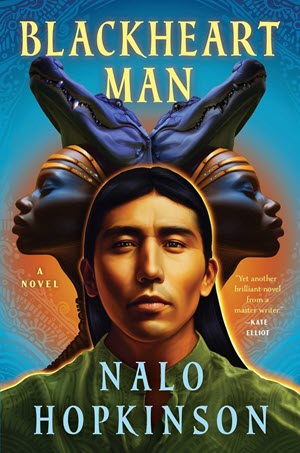

This is the June 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Blackheart Man

Blackheart Man The Folded Sky

The Folded Sky The Ministry of Time

The Ministry of Time The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses

The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses Immaculate Forms

Immaculate Forms Urban Fantasy

Urban Fantasy Hay Literary Festival, 2025

Hay Literary Festival, 2025 Testosterone Rex

Testosterone Rex Doctor Who 15.2

Doctor Who 15.2 This issue’s cover uses the art that Ben Baldwin did for the latest Chaz Brenchley Crater School book: Radhika Rages at the Crater School. The cricket match depicted plays a major role in the story.

This issue’s cover uses the art that Ben Baldwin did for the latest Chaz Brenchley Crater School book: Radhika Rages at the Crater School. The cricket match depicted plays a major role in the story.

A new Nalo Hopkinson novel is always a treat to look forward to. I’ve known that Hopkinson has been working on this one for many years. Sadly life has got in the way and slowed her production, but the book is now available and already picking up accolades. It is

A new Nalo Hopkinson novel is always a treat to look forward to. I’ve known that Hopkinson has been working on this one for many years. Sadly life has got in the way and slowed her production, but the book is now available and already picking up accolades. It is

This is the third book set in Elizabeth Bear’s White Space universe. Unlike her fantasy work, which seems to come neatly packages in trilogies, these books more or less stand on their own. I’m pretty sure that you could read The Folded Sky without having read the other two books. You’d soon pick up on how the universe works and the various bits of futuristic technology involved. At least I hope that’s the case, because I want Bear to produce more of these books. They are very fine Space Opera.

This is the third book set in Elizabeth Bear’s White Space universe. Unlike her fantasy work, which seems to come neatly packages in trilogies, these books more or less stand on their own. I’m pretty sure that you could read The Folded Sky without having read the other two books. You’d soon pick up on how the universe works and the various bits of futuristic technology involved. At least I hope that’s the case, because I want Bear to produce more of these books. They are very fine Space Opera.

This one is clearly very popular. It is being promoted heavily by Waterstones, and is a Hugo and Clarke finalist. I can see why. But, as sometimes happens, it also irritated me quite a bit. Let me explain why.

This one is clearly very popular. It is being promoted heavily by Waterstones, and is a Hugo and Clarke finalist. I can see why. But, as sometimes happens, it also irritated me quite a bit. Let me explain why.

Pleiti and Mossa are back. Hooray! I had The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses on pre-order and read it immediately it arrived. Didn’t you?

Pleiti and Mossa are back. Hooray! I had The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses on pre-order and read it immediately it arrived. Didn’t you?

The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

One of the things that often infuriates me about academic books on SF is the insistence that so many academics (usually men) have on rigidly defining genres, and then tying themselves in increasingly convoluted knots trying to make actual books fit the tiny pigeonholes that they have constructed for them. It is therefore a delight to read an academic book that calmly accepts the fact that authors will continually seek to create new approaches to their fiction.

One of the things that often infuriates me about academic books on SF is the insistence that so many academics (usually men) have on rigidly defining genres, and then tying themselves in increasingly convoluted knots trying to make actual books fit the tiny pigeonholes that they have constructed for them. It is therefore a delight to read an academic book that calmly accepts the fact that authors will continually seek to create new approaches to their fiction.

The chances of getting good SF&F writers at Hay are very slim, but you do get good history and feminism writers, and anyway it is just over the mountains from me, so I figured I should go and support the general idea of books.

The chances of getting good SF&F writers at Hay are very slim, but you do get good history and feminism writers, and anyway it is just over the mountains from me, so I figured I should go and support the general idea of books. Originally published on Cheryl’s Mewsings in April 2017

Originally published on Cheryl’s Mewsings in April 2017

Oh dear, all Doctor Who fandom is plunged into war once again.

Oh dear, all Doctor Who fandom is plunged into war once again.

This is the May 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the May 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Alien Clay

Alien Clay Tomb of Dragons

Tomb of Dragons The Vengeance

The Vengeance Rowany de Vere and a Fair Degree of Frost

Rowany de Vere and a Fair Degree of Frost Eastercon 2025

Eastercon 2025 Science Fiction in the Atomic Age

Science Fiction in the Atomic Age Llandeilo Lit Fest, 2025

Llandeilo Lit Fest, 2025 AWWE Conference, 2025

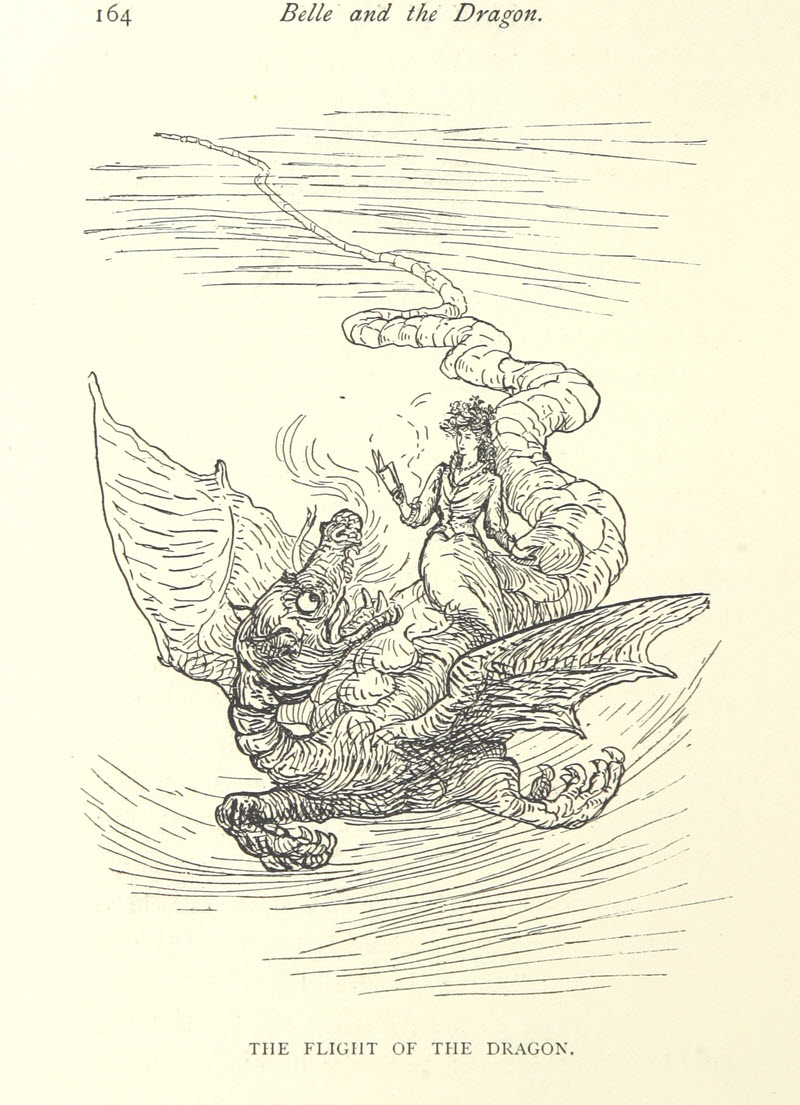

AWWE Conference, 2025 Continuing our tour of the online archives of the British Library, this issue’s cover is an illustration from Belle and the Dragon: An Elfin Comedy, a children’s book published in 1894 and written by none other than the famous Occultist, A E Waite (he of the Rider-Waite Tarot deck).

Continuing our tour of the online archives of the British Library, this issue’s cover is an illustration from Belle and the Dragon: An Elfin Comedy, a children’s book published in 1894 and written by none other than the famous Occultist, A E Waite (he of the Rider-Waite Tarot deck).

Does anyone manage to keep up with Adrian Tchaikovsky? His output is staggering. These days it seems like he’s not just writing with four pairs of hands, he must have a whole nest full of baby spiders writing for him as well.

Does anyone manage to keep up with Adrian Tchaikovsky? His output is staggering. These days it seems like he’s not just writing with four pairs of hands, he must have a whole nest full of baby spiders writing for him as well.

I’m a big fan of Katherine Addison’s Witness for the Dead books, so I immediately pounced on the new one when it came out. The title, Tomb of Dragons, is a bit of a spoiler, given that Celahar is always involved with the dead, but there is a lot more going on in the book.

I’m a big fan of Katherine Addison’s Witness for the Dead books, so I immediately pounced on the new one when it came out. The title, Tomb of Dragons, is a bit of a spoiler, given that Celahar is always involved with the dead, but there is a lot more going on in the book.

One of the joys of this year’s Eastercon was finding a new Emma Newman novel in the Dealers’ Room. Newman has been busy doing other stuff for a while, but I’m pleased to see that she hasn’t lost her touch.

One of the joys of this year’s Eastercon was finding a new Emma Newman novel in the Dealers’ Room. Newman has been busy doing other stuff for a while, but I’m pleased to see that she hasn’t lost her touch.

It is, perhaps, a little dodgy for me to be reviewing a Chaz Brenchley book featuring Rowany de Vere. However, this is not a Crater School book. It is a novella published by NewCon press. Some explanation is in order.

It is, perhaps, a little dodgy for me to be reviewing a Chaz Brenchley book featuring Rowany de Vere. However, this is not a Crater School book. It is a novella published by NewCon press. Some explanation is in order.

This year’s Eastercon took us back to Belfast and the site of the 2019 Eurocon. I’ve come to love Belfast as a city, so I was keen to go, even though the post-Brexit bureaucracy surrounding getting goods in and out of Northern Ireland made having a dealer’s table impossible.

This year’s Eastercon took us back to Belfast and the site of the 2019 Eurocon. I’ve come to love Belfast as a city, so I was keen to go, even though the post-Brexit bureaucracy surrounding getting goods in and out of Northern Ireland made having a dealer’s table impossible. I have enjoyed Adrian Munsey’s two previous forays into SF&F documentaries. The original series looked in some detail at British writers of children’s fiction in the 19th Century. It covered famous names such as JM Barrie, AA Milne, Beatrix Potter and, of course, Tolkien, but also some less well-known writers. Unusually it looked at the lives of the writers, to see how their particular circumstances might have influence what they wrote.

I have enjoyed Adrian Munsey’s two previous forays into SF&F documentaries. The original series looked in some detail at British writers of children’s fiction in the 19th Century. It covered famous names such as JM Barrie, AA Milne, Beatrix Potter and, of course, Tolkien, but also some less well-known writers. Unusually it looked at the lives of the writers, to see how their particular circumstances might have influence what they wrote. Here in rural Carmarthenshire we have our own little literary festival. It is very Welsh, and there is little in the way of speculative literature at the moment. I plan to change that, but for now I’m just attending to hear interesting stuff, and to sell books.

Here in rural Carmarthenshire we have our own little literary festival. It is very Welsh, and there is little in the way of speculative literature at the moment. I plan to change that, but for now I’m just attending to hear interesting stuff, and to sell books. I was somewhat surprised, last year, to discover that there was such a thing as the Association for Welsh Writing in English. Jo Lambert told me about it. People at Aberystwyth University were encouraging her to go. It looked like a serious literary event, but I offered them a paper on Nicola Griffith’s Spear and it got accepted, so I went.

I was somewhat surprised, last year, to discover that there was such a thing as the Association for Welsh Writing in English. Jo Lambert told me about it. People at Aberystwyth University were encouraging her to go. It looked like a serious literary event, but I offered them a paper on Nicola Griffith’s Spear and it got accepted, so I went.

This is the March 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the March 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Written on the Dark

Written on the Dark Loka

Loka Future’s Edge

Future’s Edge Mediaeval Women

Mediaeval Women Navigational Entanglements

Navigational Entanglements The Tusks of Extinction

The Tusks of Extinction The Many Selves of Katherine North

The Many Selves of Katherine North The Wild Robot

The Wild Robot The War of the Rohirrim

The War of the Rohirrim This issue’s cover from the British Library’s online collection is an illustration for a novel called Fifteen Hundred Miles an Hour (The story of a visit to the planet Mars.) by Charles Dixon. It was published by Bliss, Sands & Co in 1895. The artist is Arthur Layard.

This issue’s cover from the British Library’s online collection is an illustration for a novel called Fifteen Hundred Miles an Hour (The story of a visit to the planet Mars.) by Charles Dixon. It was published by Bliss, Sands & Co in 1895. The artist is Arthur Layard.

A new Guy Gavriel Kay novel is always a cause for excitement in these parts. I love history, and I love the way that Kay makes use of it in constructing not-quite-historical novels. Kay’s last few books have been set in the Mediterranean, originally inspired by a visit to Croatia and learning about that country’s history. The cycle also encompassed the war between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, and the condottiere of Renaissance Italy. I will miss Folco d’Acorsi, but there are other stories to be told.

A new Guy Gavriel Kay novel is always a cause for excitement in these parts. I love history, and I love the way that Kay makes use of it in constructing not-quite-historical novels. Kay’s last few books have been set in the Mediterranean, originally inspired by a visit to Croatia and learning about that country’s history. The cycle also encompassed the war between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, and the condottiere of Renaissance Italy. I will miss Folco d’Acorsi, but there are other stories to be told.

This book is a more-or-less direct sequel to Meru, though set some 16 years into the future. Some spoilers are inevitable, so if you have not read Meru yet you may want to look away.

This book is a more-or-less direct sequel to Meru, though set some 16 years into the future. Some spoilers are inevitable, so if you have not read Meru yet you may want to look away.

The latest offering from Gareth L Powell is a fast-paced space opera with multiple themes. A little background is required to explain what goes on.

The latest offering from Gareth L Powell is a fast-paced space opera with multiple themes. A little background is required to explain what goes on.

Those of you who follow me on BlueSky will remember me posting about my visit to the Mediaeval Women exhibition at the British Library. As social media is rather ephemeral, I will recap some of what I said here, but mainly this is a review of the book of the exhibition.

Those of you who follow me on BlueSky will remember me posting about my visit to the Mediaeval Women exhibition at the British Library. As social media is rather ephemeral, I will recap some of what I said here, but mainly this is a review of the book of the exhibition.