And breathe! The convention circuit is over for the year.

And breathe! The convention circuit is over for the year.

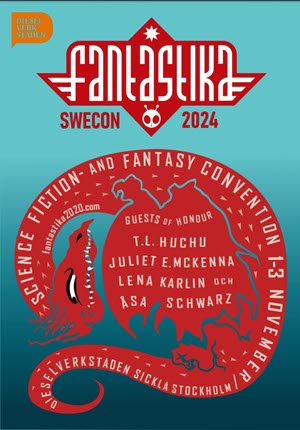

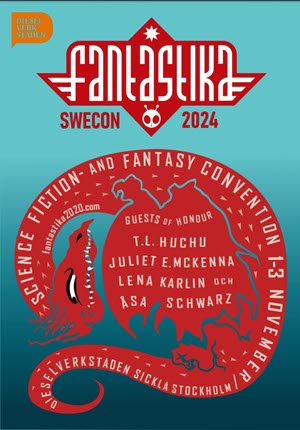

Not that I would have missed Fantastika. While I have been to many Finnish conventions, and made many Swedish friends as a result, I haven’t been to Stockholm since 2011. I did got to the Eurocon in Uppsala last year, but that just gave me an appetite for visiting Sweden again.

My trip out was a screaming disaster. On the night before I was due to fly I got email from KLM telling me that my flight had been cancelled and they had re-booked me on a later flight that did not get into Arlanda until 23:20. As it turned out, the flight has not been cancelled, but it was overbooked and I had been bumped. I have been promised compensation, and I hope I am actually able to get it. Due to the late arrival, I had to get a cab from Arlanda to the hotel, which was eye-wateringly expensive. Also we ran into roadworks on the E4 on the way in. Thankfully the driver turned off the meter while we were sat there, or the fare would have probably hit four figures in GBP.

The hotel was very lovely, though being Swedish the rooms had very little furniture and it was all wooden. Also there was no coffee service in the rooms. I did get some time to work, and I spent much of it down in the lobby where there was a free coffee service and long desks with comfy chairs and power points.

An unusual feature of the hotel was that they served a free meal each night. There was very little choice, though each individual item was served separately so if, for example, you didn’t want a particular vegetable, or a sauce, you didn’t have to have it. I managed to eat there happily most nights, but I can imagine that it would have been a lot more difficult for folks with allergies.

The convention was not in central Stockholm (which would have bene much more expensive), but in a suburb called Sickla. The space we used was in a cultural centre that was conveniently across a small square from the hotel. It contained a bar, a café, and a library as well as meeting space (some of which seemed to double as a concert/theatre venue). There was a cinema next door, and a shopping mall nearby. I’m told that the space was cheap to rent. Possibly it was subsidized by the local council.

Public transit in Stockholm is excellent. Sickla’s main tram stop, which is a terminus, was being renovated, so we had to use a temporary stop further along the line. It was very easy to navigate once you knew where everything was, but was probably a bit daunting if you arrived by tram, especially as it was uphill all the way to the hotel.

Other than love of travel, my primary reason for going was because Juliet McKenna was a Guest of Honour, and as a responsible publisher I do try to support my best-selling author. Of course, thanks to Brexit, it wasn’t possible for me to take books to Sweden to sell. However, a Swedish bookstore was able to order some from the UK and, being familiar with the tax issues, was happy to deal with importing them. The seemed to sell well.

I would have been perfectly happy to sell ebook copies of The Green Man’s War, but the Swedish fans seems uninterested in ebooks. Either that or they were unfamiliar with Juliet’s work and wanted to start with the first book in the series. In the latter case, I’m hopping that they’ll soon be hooked.

My first panel was on Friday night, and was about Strong Female Characters. I was happy to be able to use this it tell people about Fight Like A Girl 2, but I do think that we should be beyond this sort of panel by now. I did a bit of research for the panel and discovered that CL Moore’s first Jirel of Joiry story was published in 1934. That’s 90 year ago, and people are still surprised when a fantasy book has a woman with agency as the protagonist.

Having said that, I do think that there has been a change in recent years, and I think that is because the Romance genre has discovered fantasy. We now have Paranormal Romance and Romantasy as top selling subgenres, which means that everyone is SF&F is forced top notice how well Romance sells.

On Saturday I chaired a panel on The Dispossessed, one of my favourite books, which is now 50 years old. We had an excellent panel with 4 people who knew the book very well, and thanks to Saga for showing that you don’t have to be ancient to know about it. One question I didn’t get to, but which we had discussed in the Green Room beforehand, was whether the book would sell to a mainstream publisher these days. Sadly we all agreed that it would have no chance.

First up on Sunday was a panel entitled “Herding cats”, which was all about how to moderate a panel. Again we had a good group of people, but for some reason the programming folks chose to give us a moderator who had never moderated a panel before. Of course we were all very supportive, and Timothy you did a great job. Hopefully you learned a lot.

Finally I got to do a gig with Juliet. We had been asked to talk amongst ourselves on the state of publishing today. It was a pretty grim subject, and the audience seemed to go away with a much better understanding of how bad things are. Quite why anyone wants to be an author these days, I do not know. Though it is probably not as daft as wanting to be a publisher.

As I’m getting old and don’t know how much more foreign travel I will be able to do, I decided to spent a couple of days in Stockholm after the convention. There are a lot of great museums. I finally got to see the Vasa, which is a jaw-dropping sight when you first enter the vast hall where it is kept. I also spent a lot of time in the Viking Museum and learned a few things. These two and the Abba Musuem – another must see for folks of my generation – were all in the same large park, along with several other museums. I did not get to the Museum of Nordic Life, or to the Museum of Swedish Drinking Culture (which promised free samples). Honestly, I could have spent a week there.

But that is Sweden done for a while. Next year’s Swecon is in the city of Lund, and it is in October so I will not have time to go.

Adwaith are a three-piece all-girl band from South Wales. They were founded by Hollie Singer and Gwenllian Anthony, who were school friends in Carmarthen. With a couple of successful albums behind them, some appearances at Glastonbury, and support work for the likes of the Manics and Idles, they have done that thing that many newly successful bands do: spend two years in the studio.

Adwaith are a three-piece all-girl band from South Wales. They were founded by Hollie Singer and Gwenllian Anthony, who were school friends in Carmarthen. With a couple of successful albums behind them, some appearances at Glastonbury, and support work for the likes of the Manics and Idles, they have done that thing that many newly successful bands do: spend two years in the studio.

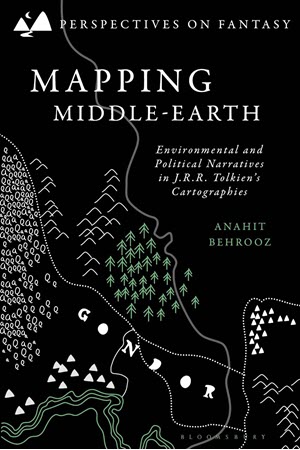

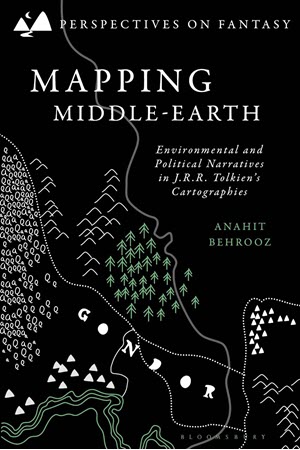

One of many great things about the Perspectives on Fantasy series from the Glasgow University Fantasy Centre is that their contract with Bloomsbury requires the publisher to produce paperback editions at affordable prices. You have to wait a year from initial publication for the paperback to appear, but once it has you should be able to get it for around £25. Or, having waited a year already, you can wait a little longer for Bloomsbury to have a sale. Which is how I ended up getting a copy of Mapping Middle Earth for just over £20.

One of many great things about the Perspectives on Fantasy series from the Glasgow University Fantasy Centre is that their contract with Bloomsbury requires the publisher to produce paperback editions at affordable prices. You have to wait a year from initial publication for the paperback to appear, but once it has you should be able to get it for around £25. Or, having waited a year already, you can wait a little longer for Bloomsbury to have a sale. Which is how I ended up getting a copy of Mapping Middle Earth for just over £20.

I’m going to make a new movie list called “One-Watch Masterpieces”, and I’ll tell you why. There’s not many lists out there like that. Sure, there’s probably a

I’m going to make a new movie list called “One-Watch Masterpieces”, and I’ll tell you why. There’s not many lists out there like that. Sure, there’s probably a

When people think of the Celtic religious calendar (which is largely a modern artefact), they tend to think in terms of Irish festivals. Thus February 1st is known as Imbolc (or for Christians, Saint Brigid’s Day). But Wales has its own traditions which do not map exactly onto the Irish ones, and which have their own names.

When people think of the Celtic religious calendar (which is largely a modern artefact), they tend to think in terms of Irish festivals. Thus February 1st is known as Imbolc (or for Christians, Saint Brigid’s Day). But Wales has its own traditions which do not map exactly onto the Irish ones, and which have their own names.

I don’t often post magazine reviews here, but Fantasy News & Lifestyle is new and from Germany. There are seven issues available in German, but the two most recent are also in English. So what’s going on in Fantasy in Germany?

I don’t often post magazine reviews here, but Fantasy News & Lifestyle is new and from Germany. There are seven issues available in German, but the two most recent are also in English. So what’s going on in Fantasy in Germany?

OK, so Hugo voting is now open. So is the Locus Poll. I should have some thoughts, despite the fact that I still have a whole lot of books that I want to read.

OK, so Hugo voting is now open. So is the Locus Poll. I should have some thoughts, despite the fact that I still have a whole lot of books that I want to read.

Well I can’t say that y’all didn’t warn me. But I watched it anyway. You were right, Section 31 is terrible. Let me count the ways…

Well I can’t say that y’all didn’t warn me. But I watched it anyway. You were right, Section 31 is terrible. Let me count the ways…

This is the January 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the January 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. We Are All Ghosts in the Forest

We Are All Ghosts in the Forest Triggernometry Finals

Triggernometry Finals Sundown in San Ojuela

Sundown in San Ojuela The New Moon’s Arms

The New Moon’s Arms Skeleton Crew

Skeleton Crew Aquaman 2

Aquaman 2 What If? – Season 3

What If? – Season 3 Editorial – January 2025

Editorial – January 2025 This issue we continue with the new practice of finding covers amongst the British Library’s collection of illustrations from old books. The picture in question was included in a 1893 novel called

This issue we continue with the new practice of finding covers amongst the British Library’s collection of illustrations from old books. The picture in question was included in a 1893 novel called

In the east of Estonia, not too far from the Russian border, is a small village. When the world fell apart, and she could no longer earn a living as a photographer, Katerina went there to live there because the village had been her grandmother’s home. There was a house there she could have. And perhaps neighbours.

In the east of Estonia, not too far from the Russian border, is a small village. When the world fell apart, and she could no longer earn a living as a photographer, Katerina went there to live there because the village had been her grandmother’s home. There was a house there she could have. And perhaps neighbours.

All good things must come to an end. In the case of an extended pun that has already produced two short books, Triggernometry is probably more overdue than most. And yet, somehow Stark Holborn has managed to squeeze a little more life out of a very silly idea.

All good things must come to an end. In the case of an extended pun that has already produced two short books, Triggernometry is probably more overdue than most. And yet, somehow Stark Holborn has managed to squeeze a little more life out of a very silly idea.

Horror is not normally my thing. I very rarely read it. But the prospect of a book by a Mexican trans woman was too much to resist. Besides, MM Olivas has been mentored by none other than Nalo Hopkinson. She has to be good, right?

Horror is not normally my thing. I very rarely read it. But the prospect of a book by a Mexican trans woman was too much to resist. Besides, MM Olivas has been mentored by none other than Nalo Hopkinson. She has to be good, right?

I was looking for some SF&F to recommend to some local PoC friends, and naturally one of my first thoughts was of Nalo Hopkinson. Given that said friends are also a lesbian couple, and one is from the Caribbean, I zeroed in on The New Moon’s Arms. Then I discovered that I had never reviewed it, so I re-read the whole thing.

I was looking for some SF&F to recommend to some local PoC friends, and naturally one of my first thoughts was of Nalo Hopkinson. Given that said friends are also a lesbian couple, and one is from the Caribbean, I zeroed in on The New Moon’s Arms. Then I discovered that I had never reviewed it, so I re-read the whole thing.

Kudos, I guess, to the Star Wars folks for trying something different. And lots of people seem to have enjoyed Skeleton Crew. My take on it is somewhat more ambivalent.

Kudos, I guess, to the Star Wars folks for trying something different. And lots of people seem to have enjoyed Skeleton Crew. My take on it is somewhat more ambivalent. I did not go to see this film in the cinema. I waited to buy it on disc until it was a bit cheaper. I did not have high expectations, but I hoped that there would be more giant war crabs.

I did not go to see this film in the cinema. I waited to buy it on disc until it was a bit cheaper. I did not have high expectations, but I hoped that there would be more giant war crabs. This is the final season of Marvel’s What If? animation series, and not before time because the creative team has clearly run out of steam. Where the series used to do interesting things with existing parts of the MCU, it has now been relegating largely to promoting forthcoming bad ideas (Thunderbolts) and past disasters (Eternals).

This is the final season of Marvel’s What If? animation series, and not before time because the creative team has clearly run out of steam. Where the series used to do interesting things with existing parts of the MCU, it has now been relegating largely to promoting forthcoming bad ideas (Thunderbolts) and past disasters (Eternals).

This is the November 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the November 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Tapestry of Time

The Tapestry of Time The Nightward

The Nightward Welsh Giants, Ghosts and Goblins

Welsh Giants, Ghosts and Goblins Helen Brady Interview

Helen Brady Interview Fantastika 2024

Fantastika 2024 Agatha All Along

Agatha All Along Deadpool and Wolverine

Deadpool and Wolverine There’s a change of policy with the cover art this issue. Sadly the free art on PixaBay has been swamped by AI crap, and there doesn’t appear to be any easy way to filter it out in searches. So instead I am using art from the public domain images collection of the British Library. The plan is to find illustrations from science fiction and fantasy books. I hope you’ll find the results interesting.

There’s a change of policy with the cover art this issue. Sadly the free art on PixaBay has been swamped by AI crap, and there doesn’t appear to be any easy way to filter it out in searches. So instead I am using art from the public domain images collection of the British Library. The plan is to find illustrations from science fiction and fantasy books. I hope you’ll find the results interesting.

I’m a sucker for a good secret history. There are, of course, a lot of bad ones out there, but I’m happy to report that the latest novel from Kate Heartfield is a fine example of the genre.

I’m a sucker for a good secret history. There are, of course, a lot of bad ones out there, but I’m happy to report that the latest novel from Kate Heartfield is a fine example of the genre.

I’m delighted to see the career of RSA Garcia flourishing. Aside from her being an SF&F author, we talk a lot about cricket on social media. She won this year’s Sturgeon Award for ‘Tantie Merle and the Farmhand 4200’, an engaging tale of an old lady, a farm robot and a goat. The Nightward is her second novel. The first was Lex Talionis, about which I interviewed her for Ujima Radio some ten years ago.

I’m delighted to see the career of RSA Garcia flourishing. Aside from her being an SF&F author, we talk a lot about cricket on social media. She won this year’s Sturgeon Award for ‘Tantie Merle and the Farmhand 4200’, an engaging tale of an old lady, a farm robot and a goat. The Nightward is her second novel. The first was Lex Talionis, about which I interviewed her for Ujima Radio some ten years ago.

Waterstones has an award for Welsh Book of the Year. Who knew? Not me, until this year, when the winning title was clearly something of interest to me. Much of the credit here should go to Stephanie Burgis who has been enthusing about the book for some time. I think she also knows the author, Claire Fayers.

Waterstones has an award for Welsh Book of the Year. Who knew? Not me, until this year, when the winning title was clearly something of interest to me. Much of the credit here should go to Stephanie Burgis who has been enthusing about the book for some time. I think she also knows the author, Claire Fayers.

Helen L Brady is a new addition to the Wizard’s Tower stable. Here Cheryl talks to Helen about her career in screenwriting and why she has moved into novels instead. They also touch on Helen’s work in costuming for theatre, and her past in historical re-enactment. Helen also talks about her first experiences of science fiction conventions at Worldcon and Bristolcon.

Helen L Brady is a new addition to the Wizard’s Tower stable. Here Cheryl talks to Helen about her career in screenwriting and why she has moved into novels instead. They also touch on Helen’s work in costuming for theatre, and her past in historical re-enactment. Helen also talks about her first experiences of science fiction conventions at Worldcon and Bristolcon. And breathe! The convention circuit is over for the year.

And breathe! The convention circuit is over for the year. If you look carefully at the poster for the TV series that accompanies this review, you will see that it says at the top, “From the twisted minds that brought you WandaVision”. Never a truer word…

If you look carefully at the poster for the TV series that accompanies this review, you will see that it says at the top, “From the twisted minds that brought you WandaVision”. Never a truer word… Team-up movies are the bro version of enemies-to-lovers lesbian romances. You put two lads with very different personalities together. They fight a lot. And they end up sharing a beer and slapping each other on the back in a just good friends really sort of way.

Team-up movies are the bro version of enemies-to-lovers lesbian romances. You put two lads with very different personalities together. They fight a lot. And they end up sharing a beer and slapping each other on the back in a just good friends really sort of way.

This is the October 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the October 2024 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Moonlight Market

The Moonlight Market The Knife and the Serpent

The Knife and the Serpent On the Economics of Small Presses

On the Economics of Small Presses BristolCon 2024

BristolCon 2024 The Sheep Look Up

The Sheep Look Up The Wood at Midwinter

The Wood at Midwinter Rings of Power – Season 2

Rings of Power – Season 2 FantasyCon 2024

FantasyCon 2024 This month’s cover is the art that Ben Baldwin did for Juliet McKenna’s latest novel, The Green Man’s War. Each time we do a new Green Man book, Ben seems to out-do himself in cover quality. We are so very lucky to have him.

This month’s cover is the art that Ben Baldwin did for Juliet McKenna’s latest novel, The Green Man’s War. Each time we do a new Green Man book, Ben seems to out-do himself in cover quality. We are so very lucky to have him.

Joanne Harris is, of course, a hugely well-known and respected writer of mainstream fiction. She’s a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, which is not the sort of honour that is doled out to hoi polloi of genre like us. And yet, she turns up at conventions. She was at Worldcon in Glasgow, and she’s a Guest of Honour at this year’s BristolCon. I first met her at FantasyCon the previous time it was in Chester.

Joanne Harris is, of course, a hugely well-known and respected writer of mainstream fiction. She’s a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, which is not the sort of honour that is doled out to hoi polloi of genre like us. And yet, she turns up at conventions. She was at Worldcon in Glasgow, and she’s a Guest of Honour at this year’s BristolCon. I first met her at FantasyCon the previous time it was in Chester.

If I need something that will be a quick and entertaining read, not too challenging or depressing, I know I can always rely on Tim Pratt. Their books are inventive, amusing, and contain just enough mild peril to keep you reading. The books also tend to include a few queer characters, Pratt being genderfluid, which is nice.

If I need something that will be a quick and entertaining read, not too challenging or depressing, I know I can always rely on Tim Pratt. Their books are inventive, amusing, and contain just enough mild peril to keep you reading. The books also tend to include a few queer characters, Pratt being genderfluid, which is nice.

At World Fantasy this year, Scott Andrews of Beneath Ceaseless Skies gave

At World Fantasy this year, Scott Andrews of Beneath Ceaseless Skies gave  The Green Man’s War is currently available for pre-order (

The Green Man’s War is currently available for pre-order ( This year saw the 15th iteration of BristolCon, and the first that was a whole weekend long rather than just Saturday. Con Chair MEG was upfront about this being an experiment. Lots of people had asked for it, but the only way to know if it would work was to try it.

This year saw the 15th iteration of BristolCon, and the first that was a whole weekend long rather than just Saturday. Con Chair MEG was upfront about this being an experiment. Lots of people had asked for it, but the only way to know if it would work was to try it. This review was first published

This review was first published

When Susanna Clarke produces a novel it makes a huge amount of money for Bloomsbury. Naturally they would love her to do so regularly. Probably more so now as their other best-selling author is doing everything she can to trash her own reputation. But Clarke seems to produce novels only once a decade. Therefore, Bloomsbury will push out absolutely anything as the new Susanna Clarke book, as long as it is something she has written. If she sent them her shopping list, they would probably publish that.

When Susanna Clarke produces a novel it makes a huge amount of money for Bloomsbury. Naturally they would love her to do so regularly. Probably more so now as their other best-selling author is doing everything she can to trash her own reputation. But Clarke seems to produce novels only once a decade. Therefore, Bloomsbury will push out absolutely anything as the new Susanna Clarke book, as long as it is something she has written. If she sent them her shopping list, they would probably publish that.

Amazon’s Tolkien vehicle continues to be Marmite for fans. I’ve seen some people who have been hate-watching it, and others who love it to pieces. There doesn’t seem to be much in between.

Amazon’s Tolkien vehicle continues to be Marmite for fans. I’ve seen some people who have been hate-watching it, and others who love it to pieces. There doesn’t seem to be much in between. I hadn’t been intending to go to FantasyCon this year because October was busy enough already. Or, at least, I didn’t think I had a membership and I wasn’t going to buy one. Then, about a month before the convention, I got sent some programme assignments. I hastily checked with the con, and lo, I did have a membership. I must have bought it last year and then forgotten about it. The programme assignments sounded interesting, and Chester is a great place to visit, so I decided to go.

I hadn’t been intending to go to FantasyCon this year because October was busy enough already. Or, at least, I didn’t think I had a membership and I wasn’t going to buy one. Then, about a month before the convention, I got sent some programme assignments. I hastily checked with the con, and lo, I did have a membership. I must have bought it last year and then forgotten about it. The programme assignments sounded interesting, and Chester is a great place to visit, so I decided to go.