The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

Much of the commentary around the issue also maintains that we (that is humans) have always known the difference between men and women. It also maintains that the definitive test for femininity is the possession of XX chromosomes, as opposed to XY for men. This is despite the fact that sex chromosomes have only been known to science since 1905, and that many humans are known to have chromosome patterns that are neither XX nor XY.

Of course if you are an historian who specializes in gender diversity (which I am) it is important to understand how people in the past understood sex and gender. There is no greater expert on such issues than Helen King. She’s a Classicist by training, and Professor Emerita at the Open University. Her particular specialty is the history of medicine, and her latest book, Immaculate Forms, takes her on a quest to understand how the female body was understood from ancient times until now.

King has structured the book in four main sections, each of which looks at four supposedly feminine body parts: the breasts, the hymen, the clitoris and the womb. I’ll follow her structure here.

Breasts are, of course, the most obvious signifier of womanhood, being both large and visible. It is significant, therefore, that the anti-trans movement has made it an article of faith that only cis women can have them. Trans women, they claim, can only gain breasts through having implants. King knows better. Breast tissue is common to both men and women, and with appropriate doses of hormones trans women not only grow breasts, but can lactate. I have been roundly ridiculed on social media by TERFs for stating this, so it is something of a pleasure to have support from Professor King.

Men are also deeply obsessed with breasts, for entirely different reasons. King does a fine job of showing how, down the centuries, male doctors found excuses to fondle women’s breasts, and even sample their milk, all in the name of ‘science’. The clergy have had a harder time of it. Did the Virgin Mary have breasts? If so, did she lactate, and did baby Jesus suckle? For some that was just too icky to contemplate.

Whereas breasts are famed for their visibility, the hymen may not exist at all. King refrains from coming down on either side of the debate, if only because hymen-replacement surgery for divorced women is now apparently big business in certain parts of America. If the hymen did not exist in the past, it certainly does now. And, whether or not it did exist, the concept of the hymen has had a massive influence on women’s lives through history.

In contrast, we can be certain that the clitoris exists now, because so many male doctors claim to have been the first person to discover it, rather in the manner that Columbus claimed to have discovered the Americas. Women, like the indigenous Americans, have known where it is all the time.

Of all the female organs, the womb is undoubtedly the most powerful. Not only is it responsible for nurturing new life, it has also been accused of being the source of all manner of female ailments down the years. Hysteria, anyone?

Well actually no. The ancients were big on how the womb might wander around the body, and how it might get hungry and angry if it were not made pregnant on a regular basis. However, the mental illness of hysteria, which we now associate solely with women, was once a more general condition.

King reveals that the term was coined as a mental illness in 18th Century France. Frightened aristocrats found that, if they were diagnosed with a mental illness and confined to a nursing home, they might be spared the guillotine. Hysteria only became a women-only condition after WWI because it was felt that diagnosing soldiers with such a term impugned their masculinity; so ‘shell-shock’ was coined as an alternative.

While a certain type of man only values women as long as he can make them pregnant, we now know that even possessing a womb is not a definitive indicator of womanhood. King notes:

Of course, not all women have a womb; some are born without one, others lose it to surgery, and others have transitioned to being women.

For those wanting more background, the intersex variation that results in a woman being born without a womb is called Mayer-Rotikansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. King notes that at least one such woman has successfully received a womb transplant and become pregnant using her own eggs.

So it is complicated. How one defines a ‘biological woman’ is open to debate, has changed regularly with changes in medical knowledge, and will always end up excluding some people who were assigned female at birth. King notes:

These modern methods of appealing to chromosomes and hormones, features of our embodiment that others can’t easily see and of which we are entirely unaware, can still prove far from conclusive in deciding whether someone is a man or a woman, and we rapidly revert to the evidence of our eyes. Culturally, we continue to crave binaries.

And yet…

Men and women have been set up as entirely different, with their bodies claimed as bearing clear witness to this. But one of the messages from studying bodies across history is that, while the dance between describing difference and acknowledging similarity has been going on for centuries, binaries simply don’t work.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the Supreme Court and the government continue to refuse to listen, either to history or to science.

Title:

Title: Immaculate Forms

By: Helen KingPublisher: Wellcome Collection

Purchase links:Amazon UKAmazon USBookshop.org UKSee

here for information about buying books though

Salon Futura

This is the June 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the June 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Cover: Radhika Rages at the Crater School: This issue's cover is by Ben Baldwin. It also graces the cover of the new Crater School book from Chaz Brenchley.

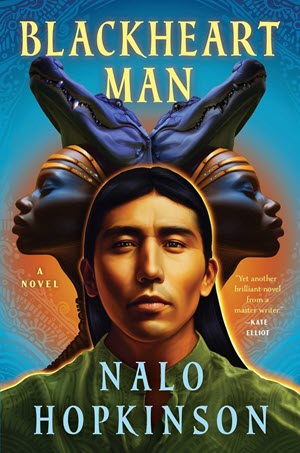

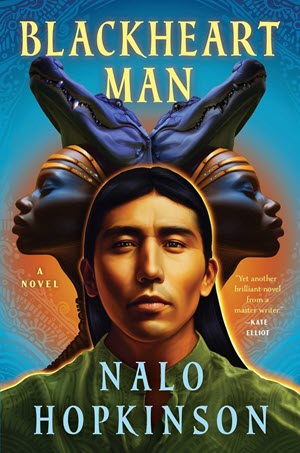

Cover: Radhika Rages at the Crater School: This issue's cover is by Ben Baldwin. It also graces the cover of the new Crater School book from Chaz Brenchley. Blackheart Man: It has been a long time coming, but the new Nalo Hopkinson novel has finally arrived

Blackheart Man: It has been a long time coming, but the new Nalo Hopkinson novel has finally arrived The Folded Sky: The latest book in Elizabeth Bear's White Space universe has pirates, some intriguing aliens, and cats

The Folded Sky: The latest book in Elizabeth Bear's White Space universe has pirates, some intriguing aliens, and cats The Ministry of Time: It is one of the most talked-about SF books of 2025, but is it any good?

The Ministry of Time: It is one of the most talked-about SF books of 2025, but is it any good? The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses: The new Pleiti and Mossa book is out, and Cheryl has pounced on it immediately

The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses: The new Pleiti and Mossa book is out, and Cheryl has pounced on it immediately Immaculate Forms: Are men and women different, and how could we tell? Helen King takes a trip into the history of body-sexing.

Immaculate Forms: Are men and women different, and how could we tell? Helen King takes a trip into the history of body-sexing. Urban Fantasy: Stefan Ekman looks deeply into what Urban Fantasy fiction is all about

Urban Fantasy: Stefan Ekman looks deeply into what Urban Fantasy fiction is all about Hay Literary Festival, 2025: In which Cheryl pays a visit to this year's Hay Literary Festival and gets a compliment from one of her feminist heroes

Hay Literary Festival, 2025: In which Cheryl pays a visit to this year's Hay Literary Festival and gets a compliment from one of her feminist heroes Testosterone Rex: Cheryl's trip to Hay reminded her of this blast from the past

Testosterone Rex: Cheryl's trip to Hay reminded her of this blast from the past Doctor Who 15.2: Another series of Doctor Who comes to an end. Which provides greater drama, the actual shows, or the online controversy about them?

Doctor Who 15.2: Another series of Doctor Who comes to an end. Which provides greater drama, the actual shows, or the online controversy about them? Editorial – June 2025: Cheryl is back from Finland and looking forward to doing less travel for a while

Editorial – June 2025: Cheryl is back from Finland and looking forward to doing less travel for a while This issue’s cover uses the art that Ben Baldwin did for the latest Chaz Brenchley Crater School book: Radhika Rages at the Crater School. The cricket match depicted plays a major role in the story.

This issue’s cover uses the art that Ben Baldwin did for the latest Chaz Brenchley Crater School book: Radhika Rages at the Crater School. The cricket match depicted plays a major role in the story.

A new Nalo Hopkinson novel is always a treat to look forward to. I’ve known that Hopkinson has been working on this one for many years. Sadly life has got in the way and slowed her production, but the book is now available and already picking up accolades. It is

A new Nalo Hopkinson novel is always a treat to look forward to. I’ve known that Hopkinson has been working on this one for many years. Sadly life has got in the way and slowed her production, but the book is now available and already picking up accolades. It is

This is the third book set in Elizabeth Bear’s White Space universe. Unlike her fantasy work, which seems to come neatly packages in trilogies, these books more or less stand on their own. I’m pretty sure that you could read The Folded Sky without having read the other two books. You’d soon pick up on how the universe works and the various bits of futuristic technology involved. At least I hope that’s the case, because I want Bear to produce more of these books. They are very fine Space Opera.

This is the third book set in Elizabeth Bear’s White Space universe. Unlike her fantasy work, which seems to come neatly packages in trilogies, these books more or less stand on their own. I’m pretty sure that you could read The Folded Sky without having read the other two books. You’d soon pick up on how the universe works and the various bits of futuristic technology involved. At least I hope that’s the case, because I want Bear to produce more of these books. They are very fine Space Opera.

This one is clearly very popular. It is being promoted heavily by Waterstones, and is a Hugo and Clarke finalist. I can see why. But, as sometimes happens, it also irritated me quite a bit. Let me explain why.

This one is clearly very popular. It is being promoted heavily by Waterstones, and is a Hugo and Clarke finalist. I can see why. But, as sometimes happens, it also irritated me quite a bit. Let me explain why.

Pleiti and Mossa are back. Hooray! I had The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses on pre-order and read it immediately it arrived. Didn’t you?

Pleiti and Mossa are back. Hooray! I had The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses on pre-order and read it immediately it arrived. Didn’t you?

The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

The question of what defines a woman is very much on people’s lips right now, especially in the UK where the Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to appeal to biology. No matter that no actual biologists were consulted, or that members of the British Medical Association have described the ruling as “scientifically illiterate”; the concept of a “biological woman” has now apparently been enshrined in UK law (if not yet in the Equality Act, over-enthusiastic compliers in advance please note).

One of the things that often infuriates me about academic books on SF is the insistence that so many academics (usually men) have on rigidly defining genres, and then tying themselves in increasingly convoluted knots trying to make actual books fit the tiny pigeonholes that they have constructed for them. It is therefore a delight to read an academic book that calmly accepts the fact that authors will continually seek to create new approaches to their fiction.

One of the things that often infuriates me about academic books on SF is the insistence that so many academics (usually men) have on rigidly defining genres, and then tying themselves in increasingly convoluted knots trying to make actual books fit the tiny pigeonholes that they have constructed for them. It is therefore a delight to read an academic book that calmly accepts the fact that authors will continually seek to create new approaches to their fiction.

The chances of getting good SF&F writers at Hay are very slim, but you do get good history and feminism writers, and anyway it is just over the mountains from me, so I figured I should go and support the general idea of books.

The chances of getting good SF&F writers at Hay are very slim, but you do get good history and feminism writers, and anyway it is just over the mountains from me, so I figured I should go and support the general idea of books. Originally published on Cheryl’s Mewsings in April 2017

Originally published on Cheryl’s Mewsings in April 2017

Oh dear, all Doctor Who fandom is plunged into war once again.

Oh dear, all Doctor Who fandom is plunged into war once again.

This is the May 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the May 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Alien Clay

Alien Clay Tomb of Dragons

Tomb of Dragons The Vengeance

The Vengeance Rowany de Vere and a Fair Degree of Frost

Rowany de Vere and a Fair Degree of Frost Eastercon 2025

Eastercon 2025 Science Fiction in the Atomic Age

Science Fiction in the Atomic Age Llandeilo Lit Fest, 2025

Llandeilo Lit Fest, 2025 AWWE Conference, 2025

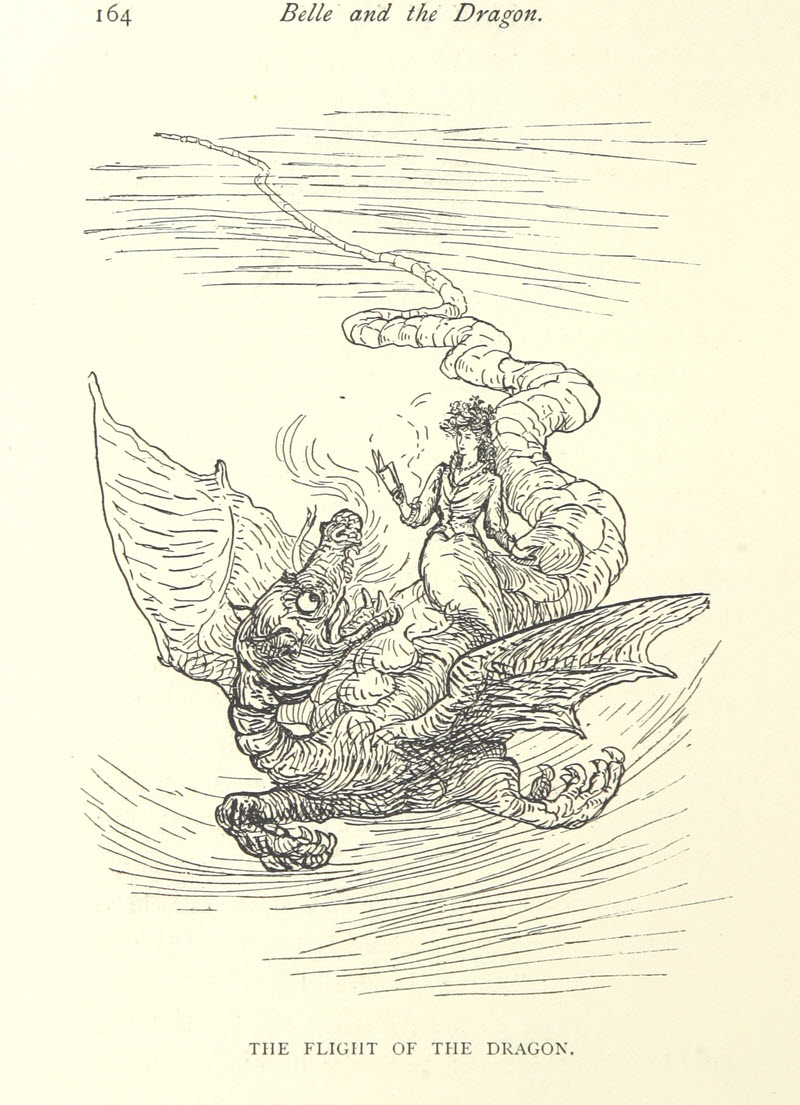

AWWE Conference, 2025 Continuing our tour of the online archives of the British Library, this issue’s cover is an illustration from Belle and the Dragon: An Elfin Comedy, a children’s book published in 1894 and written by none other than the famous Occultist, A E Waite (he of the Rider-Waite Tarot deck).

Continuing our tour of the online archives of the British Library, this issue’s cover is an illustration from Belle and the Dragon: An Elfin Comedy, a children’s book published in 1894 and written by none other than the famous Occultist, A E Waite (he of the Rider-Waite Tarot deck).

Does anyone manage to keep up with Adrian Tchaikovsky? His output is staggering. These days it seems like he’s not just writing with four pairs of hands, he must have a whole nest full of baby spiders writing for him as well.

Does anyone manage to keep up with Adrian Tchaikovsky? His output is staggering. These days it seems like he’s not just writing with four pairs of hands, he must have a whole nest full of baby spiders writing for him as well.

I’m a big fan of Katherine Addison’s Witness for the Dead books, so I immediately pounced on the new one when it came out. The title, Tomb of Dragons, is a bit of a spoiler, given that Celahar is always involved with the dead, but there is a lot more going on in the book.

I’m a big fan of Katherine Addison’s Witness for the Dead books, so I immediately pounced on the new one when it came out. The title, Tomb of Dragons, is a bit of a spoiler, given that Celahar is always involved with the dead, but there is a lot more going on in the book.

One of the joys of this year’s Eastercon was finding a new Emma Newman novel in the Dealers’ Room. Newman has been busy doing other stuff for a while, but I’m pleased to see that she hasn’t lost her touch.

One of the joys of this year’s Eastercon was finding a new Emma Newman novel in the Dealers’ Room. Newman has been busy doing other stuff for a while, but I’m pleased to see that she hasn’t lost her touch.

It is, perhaps, a little dodgy for me to be reviewing a Chaz Brenchley book featuring Rowany de Vere. However, this is not a Crater School book. It is a novella published by NewCon press. Some explanation is in order.

It is, perhaps, a little dodgy for me to be reviewing a Chaz Brenchley book featuring Rowany de Vere. However, this is not a Crater School book. It is a novella published by NewCon press. Some explanation is in order.

This year’s Eastercon took us back to Belfast and the site of the 2019 Eurocon. I’ve come to love Belfast as a city, so I was keen to go, even though the post-Brexit bureaucracy surrounding getting goods in and out of Northern Ireland made having a dealer’s table impossible.

This year’s Eastercon took us back to Belfast and the site of the 2019 Eurocon. I’ve come to love Belfast as a city, so I was keen to go, even though the post-Brexit bureaucracy surrounding getting goods in and out of Northern Ireland made having a dealer’s table impossible. I have enjoyed Adrian Munsey’s two previous forays into SF&F documentaries. The original series looked in some detail at British writers of children’s fiction in the 19th Century. It covered famous names such as JM Barrie, AA Milne, Beatrix Potter and, of course, Tolkien, but also some less well-known writers. Unusually it looked at the lives of the writers, to see how their particular circumstances might have influence what they wrote.

I have enjoyed Adrian Munsey’s two previous forays into SF&F documentaries. The original series looked in some detail at British writers of children’s fiction in the 19th Century. It covered famous names such as JM Barrie, AA Milne, Beatrix Potter and, of course, Tolkien, but also some less well-known writers. Unusually it looked at the lives of the writers, to see how their particular circumstances might have influence what they wrote. Here in rural Carmarthenshire we have our own little literary festival. It is very Welsh, and there is little in the way of speculative literature at the moment. I plan to change that, but for now I’m just attending to hear interesting stuff, and to sell books.

Here in rural Carmarthenshire we have our own little literary festival. It is very Welsh, and there is little in the way of speculative literature at the moment. I plan to change that, but for now I’m just attending to hear interesting stuff, and to sell books. I was somewhat surprised, last year, to discover that there was such a thing as the Association for Welsh Writing in English. Jo Lambert told me about it. People at Aberystwyth University were encouraging her to go. It looked like a serious literary event, but I offered them a paper on Nicola Griffith’s Spear and it got accepted, so I went.

I was somewhat surprised, last year, to discover that there was such a thing as the Association for Welsh Writing in English. Jo Lambert told me about it. People at Aberystwyth University were encouraging her to go. It looked like a serious literary event, but I offered them a paper on Nicola Griffith’s Spear and it got accepted, so I went.

This is the March 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the March 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. Written on the Dark

Written on the Dark Loka

Loka Future’s Edge

Future’s Edge Mediaeval Women

Mediaeval Women Navigational Entanglements

Navigational Entanglements The Tusks of Extinction

The Tusks of Extinction The Many Selves of Katherine North

The Many Selves of Katherine North The Wild Robot

The Wild Robot The War of the Rohirrim

The War of the Rohirrim This issue’s cover from the British Library’s online collection is an illustration for a novel called Fifteen Hundred Miles an Hour (The story of a visit to the planet Mars.) by Charles Dixon. It was published by Bliss, Sands & Co in 1895. The artist is Arthur Layard.

This issue’s cover from the British Library’s online collection is an illustration for a novel called Fifteen Hundred Miles an Hour (The story of a visit to the planet Mars.) by Charles Dixon. It was published by Bliss, Sands & Co in 1895. The artist is Arthur Layard.

A new Guy Gavriel Kay novel is always a cause for excitement in these parts. I love history, and I love the way that Kay makes use of it in constructing not-quite-historical novels. Kay’s last few books have been set in the Mediterranean, originally inspired by a visit to Croatia and learning about that country’s history. The cycle also encompassed the war between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, and the condottiere of Renaissance Italy. I will miss Folco d’Acorsi, but there are other stories to be told.

A new Guy Gavriel Kay novel is always a cause for excitement in these parts. I love history, and I love the way that Kay makes use of it in constructing not-quite-historical novels. Kay’s last few books have been set in the Mediterranean, originally inspired by a visit to Croatia and learning about that country’s history. The cycle also encompassed the war between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, and the condottiere of Renaissance Italy. I will miss Folco d’Acorsi, but there are other stories to be told.

This book is a more-or-less direct sequel to Meru, though set some 16 years into the future. Some spoilers are inevitable, so if you have not read Meru yet you may want to look away.

This book is a more-or-less direct sequel to Meru, though set some 16 years into the future. Some spoilers are inevitable, so if you have not read Meru yet you may want to look away.

The latest offering from Gareth L Powell is a fast-paced space opera with multiple themes. A little background is required to explain what goes on.

The latest offering from Gareth L Powell is a fast-paced space opera with multiple themes. A little background is required to explain what goes on.

Those of you who follow me on BlueSky will remember me posting about my visit to the Mediaeval Women exhibition at the British Library. As social media is rather ephemeral, I will recap some of what I said here, but mainly this is a review of the book of the exhibition.

Those of you who follow me on BlueSky will remember me posting about my visit to the Mediaeval Women exhibition at the British Library. As social media is rather ephemeral, I will recap some of what I said here, but mainly this is a review of the book of the exhibition.

These days Aliette de Bodard’s books are best known for their themes of Sapphic romance. That’s not really my thing, but if it wins her extra sales I’m all in favour because it means that more people are reading interesting SF.

These days Aliette de Bodard’s books are best known for their themes of Sapphic romance. That’s not really my thing, but if it wins her extra sales I’m all in favour because it means that more people are reading interesting SF.

Bringing animals back from extinction has been a fascination of science fiction at least since Jurassic Park, probably much longer. Usually what people want is dinosaurs, but the wooly mammoth also holds a significant place in the human imagination, and resurrecting it seems slightly less unlikely.

Bringing animals back from extinction has been a fascination of science fiction at least since Jurassic Park, probably much longer. Usually what people want is dinosaurs, but the wooly mammoth also holds a significant place in the human imagination, and resurrecting it seems slightly less unlikely.

This review was first published on Cheryl’s blog in June 2016.

This review was first published on Cheryl’s blog in June 2016.

Air Canada’s offerings on my trips this month were underwhelming. That wasn’t for any lack of choice. There were huge numbers of films and TV shows that I could have watched; but there were very few that I actually wanted to see. I mean, I could have re-watched the entire Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings series which, with the addition of The War of the Rohirrim, is now up to 7 films. I could have re-watched all four Matrix films. I did re-watch Jupiter Ascending, but only once out of four flights. What was lacking was something new that I actually wanted to see, and that was as much the fault of Hollywood as anyone else.

Air Canada’s offerings on my trips this month were underwhelming. That wasn’t for any lack of choice. There were huge numbers of films and TV shows that I could have watched; but there were very few that I actually wanted to see. I mean, I could have re-watched the entire Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings series which, with the addition of The War of the Rohirrim, is now up to 7 films. I could have re-watched all four Matrix films. I did re-watch Jupiter Ascending, but only once out of four flights. What was lacking was something new that I actually wanted to see, and that was as much the fault of Hollywood as anyone else. Now that the rich mine of Middle Earth has been opened up for exploitation, the corporations that have rights to exploit it are keen to do so as rapidly as possible before the movie-watching public gets bored. Rings of Power is at least nominally based on the events chronicled in The Silmarillion. The War of the Rohirrim is mostly just shameless recycling of previously used material.

Now that the rich mine of Middle Earth has been opened up for exploitation, the corporations that have rights to exploit it are keen to do so as rapidly as possible before the movie-watching public gets bored. Rings of Power is at least nominally based on the events chronicled in The Silmarillion. The War of the Rohirrim is mostly just shameless recycling of previously used material.

This is the February 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents.

This is the February 2025 issue of Salon Futura. Here are the contents. The Practice, the Horizon and the Chain

The Practice, the Horizon and the Chain Kaos

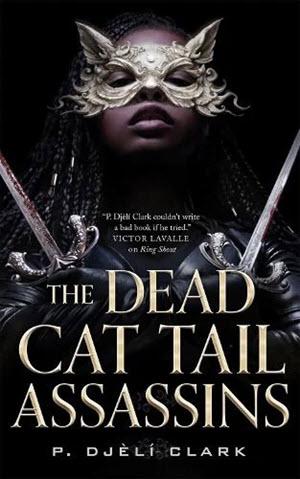

Kaos The Dead Cat Tail Assassins

The Dead Cat Tail Assassins Adwaith – Solas

Adwaith – Solas Mapping Middle Earth

Mapping Middle Earth The Substance

The Substance Gŵyl y Golau

Gŵyl y Golau Fantasy News & Lifestyle Magazine

Fantasy News & Lifestyle Magazine Hugo Voting Time

Hugo Voting Time Section 31

Section 31 Continuing our theme of raiding the free image collection provided by the British Library, here we have a fantasy-themed cover. The image is titled, ‘The Dragon’s Den’ and it comes from Among the Gnomes. An occult tale of adventure in the Untersberg by Franz Hartmann. The book was published in 1895 by T Fisher Unwin. The illustrator is known as Sedgwick, but I haven’t found out any more about them. There is a version of the book available

Continuing our theme of raiding the free image collection provided by the British Library, here we have a fantasy-themed cover. The image is titled, ‘The Dragon’s Den’ and it comes from Among the Gnomes. An occult tale of adventure in the Untersberg by Franz Hartmann. The book was published in 1895 by T Fisher Unwin. The illustrator is known as Sedgwick, but I haven’t found out any more about them. There is a version of the book available

The title of this novella from Sophia Samatar gives you no clue as to what it is about. The cover does not help. In starting to read through you understand that the book is set on a space ark of some sort. That is not what the book is about at all.

The title of this novella from Sophia Samatar gives you no clue as to what it is about. The cover does not help. In starting to read through you understand that the book is set on a space ark of some sort. That is not what the book is about at all.

I’m a bit behind with this one due to the large quantity of interesting TV demanding my time. When it first came out, my Classicist friends were absolutely delighted about it. I can see why. I can also see why it was not renewed.

I’m a bit behind with this one due to the large quantity of interesting TV demanding my time. When it first came out, my Classicist friends were absolutely delighted about it. I can see why. I can also see why it was not renewed. In the prosperous merchant city of Tal Abisi there is a flourishing trade in assassination. Among the guilds of assassins, the Dead Cat Tails are generally acknowledged to be the best. And among the Dead Cat Tails, Eveen the Eviscerator is one of their star performers. This means that she gets some of the most interesting and challenging commissions.

In the prosperous merchant city of Tal Abisi there is a flourishing trade in assassination. Among the guilds of assassins, the Dead Cat Tails are generally acknowledged to be the best. And among the Dead Cat Tails, Eveen the Eviscerator is one of their star performers. This means that she gets some of the most interesting and challenging commissions.