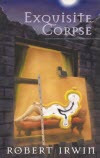

Exquisite Corpse

Sam Jordison delves into Surrealism with the help of Robert Irwin.

Britain may have given the world William Blake and Alice in Wonderland, but its generally said that its artists had missed the boat when European surrealism was cresting the waves in the 1930s. The British Surrealism movement started late and failed to produce an artist as enduring and important as Salvador Dalì. Indeed, if you’re anything like me, chances are that you’ve rarely given British Surrealism a second thought. In truth, I knew next to nothing about the movement until I read the Exquisite Corpse [Purchase] by Robert Irwin.

Even without Irwin, the British Surrealists turned out to be fascinating enough. Consider, for instance, the International Surrealist Exhibition, which took place in 1936 in London’s New Burlington Galleries. Thousands of people visited this every day — and small surprise when the artists themselves were so weird and wonderful, never mind their creations. The galleries were haunted by the ‘surrealist phantom’, a woman in a long white flowing dress, face concealed behind a veil of red roses, carrying a flower-filled model leg in one hand and a raw pork chop in another. And — naturally — there was Dalì. He arrived in a deep sea diving suit intending to deliver a lecture on ‘Fantomes paranoiaques authentiques’. He was interrupted, however, by his inability to breath. The poet David Gasgoyne had to prise off the eminent surrealist’s helmet with pliers.

It’s easy to see the appeal of this lurid spectacle against backdrop of 1930s London, drab enough because of the depression, and increasingly darkened by the gathering clouds of The Second World War. There are rich pickings there for a writer of talent — but the world that Irwin creates makes as much of an impression as the one from which he borrows. Exquisite Corpse may be situated in what most of us would call the real world, but the author has made it fantastic. As I read, I had that heady sense of breaking new ground, of the known rubbing up against the alien and disconcerting, that will be instantly recognisable to fans of genre fiction.

Quite where this feeling came from is hard to explain exactly. It may be a fantasy world — but the rules haven’t changed that much. There are no strange creatures, no miraculous technologies and no magic — unless you count the fact that the whole book purports to be “a magical trap.” The narrator, a surrealist painter called Caspar (he has no surname) claims to be writing in order to ensnare his lost love, Caroline. His method is to describe, often in excruciating and embarrassing detail, his time with her, and the period following on from her disappearance.

A good measure of the nature of Caspar’s world comes in his description of his first meeting with Caroline. It takes place in a Soho pub. Caspar is trying to experience the world as a blind man and has a sleeping mask over his eyes. He’s been taken into the pub friend by his friend MacKellar who has told him they are in Hampstead, and have entered “one of London’s most exclusive brothels”, shortly before leaving Caspar in his self-inflicted darkness. Caroline approaches Caspar with a note that MacKellar has written for her. It reads:

“Dear Miss____

You have a kindly face. I beg you take care of this tragically afflicted young man. God help me. It has all become too much for me. Thank you and God bless!His despairing father,

M”

She leads Caspar outside and tells him she works as a secretary. Caspar is entranced:

“Office work! Regular hours! Office intrigues! Office jokes! To me it was a fantasy world in miniature, a modern Lilliput, endearing in the pettiness of its concerns.”

And even by this early stage of the novel it’s clear what Caspar means. Caspar’s reality — the reality of the novel — is so far removed from what we would normally call everyday concerns that they do indeed start to seem alien. We are in a very different kind of place.

Back in the real surreal world, when the half dead Dalì emerged from the diving suit, he was unapologetic. “I just wanted to show that I was plunging deeply into the human mind,” he explained. Caspar presents a similar mix of the ridiculous and the deadly serious. He is funny. He is absurd. And yet he is conducting sober explorations of his psyche.

Caspar’s world is one lit up by the hypnagogic — surreal — images that play around his mind as he tries to contort into ever stranger nightmare shapes for the sake of his art. Its inhabitants, meanwhile, are forever playing practical jokes on each other, playing with each others minds (Caspar, for instance, has a sideline in mesmerism), goofing off, putting on that daft show at the International Surrealist Exhibition, getting drunk, smoking opium, taking trips to the seaside… Even the prose seems playful:

“However, if being nice qualified me to kiss Caroline, then I was prepared to go along with the imposture, but the truth was that I had only been standing there, holding her umbrella and handbag, as part of a long-term strategy to fuck her senseless.”

And yet, more often than not, Caspar is deadly earnest. There’s a character in the book called Clive who becomes attracted both to Caroline and the general excitement of getting to know “longhairs and bohos”, but who stays in a conventional city job. Late on he says to Caspar: “Surrealism is just a joke isn’t it? Don’t let me down on this one.” Caspar tells us that in reply: “I shook my head in vigorous denial.” Although, since this is a book that also delights in ambiguity, he can’t help but add: “… if I thought of certain cases like MacKellar, I would have to admit that Clive was at least partly right.”

There is only one occasion where there is no room for such ambiguity and no room for jokes. A place where reality conjures horrors more twisted than anything Caspar has tried to imagine for the sake of art. A place, indeed, where art reaches its limit — “a forbidden zone.” This is Belsen shortly after its liberation, where Caspar is sent to make a record in his job as a war painter.

In lesser hands, this climactic encounter with a real life nightmare might seem forced, but Irwin handles it deftly. It makes a powerful point — and a sharp one. It takes up just a few quick lines of prose and has a clear, but quietly spoken message.

Irwin shows similar facility on the many other occasions he blends known history in with Caspar’s fantastical life — although Belsen is exceptional in not being at all funny. More typical is a meeting with George Orwell, which results in a furious argument, Orwell shouting at Caspar:

“What the fuck do you paint like that for? It’s diseased, disgusting, phosphorescent in its putridity.”

Or a brief mention of JB Priestly, during a trip to the seaside, who thinks that surrealists stand for “violence and neurotic unreason,” and that they are “truly decadent”. This prompts the remark: “all this seemed particularly unfair after we had just had a bracing dip and an energetic game of beachball. Had Priestley done anything half so healthy that morning? He was probably still scraping the dottle out of that disgusting pipe of his.”

I suppose quoted out of context, these encounters seem unsubtle. You’ll have to take my word that they flow as naturally out of the book as everything else caught up in Caspar’s eloquent torrents. The challenge for me when reading the book was to work out where history ended and fiction began. I was even reduced to googling “the Serapion brotherhood”, the group to which Caspar belongs. It came as some surprise to discover that it was imaginary. Caspar may inhabit terra incognita, but it is vivid and real.

There’s similar difficulty in detecting the borderlines between reality and fantasy in Caspar’s narrative. This problem becomes all the more pressing when Caspar admits himself to an insane asylum — a place he doesn’t much like because he finds the patients “dull and ordinary by comparison with my old companions in the Serapion Brotherhood.”

I understood the feeling. The world Irwin conjures is so enchanting, so involving, that stepping out of the book is nothing less than a drag. Fortunately, there’s compensation in the conclusion. I don’t want to say more about what happens because it’s such a beautifully crafted tease. Suffice to say that it makes you want to read the whole thing all over again — and leaves you convinced that to do so will be nothing less than an exquisite pleasure.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting Salon Futura financially, either by buying from the Wizard's Tower Bookstore, or by donating money directly via PayPal.

So glad you enjoyed this, Sam – it’s one of my favourite novels of recent decades, and it puzzles me why it isn’t better known. There’s some great humour in there – the bungled orgy, and the character who believes that it is his duty, as a writer of fiction, to constantly tell lies.

Although Britain appears to have been late to the surrealist party, some of our painters do anticipate the movement to some extent – eg Edward Wadsworth and (perhaps to a lesser extent) Paul Nash.

Thanks Mike,

I agree entirely. It’s very funny, isn’t it? I’m reading Satan Wants Me at the moment as well, which is also very amusing. Robert Irwin clearly deserves a wider audience.

After reading the book I spent quite a bit of time surfing the web for pictures by British surrealists and some of them seemed pretty interesting to me.

(Useful link here: http://www.britishsurrealism.com/)